“You can’t win ’em all.”

This popular statement is relevant in the world of gaming, but not exactly as one might think. Sure, you win some and you lose some in competitive games, but not all games are meant to be “won.” Rather, many games are meant to simply be experienced from beginning to end, with little concern for concepts such as success and failure.

In the modern gaming era, fewer single-player games can be, to use archaic gamer terminology, beaten. Videogame narratives are typically predetermined, with each possessing a natural flow from a definite beginning to a definite end. There is rarely, if ever, a final, losing state. A game would have to forbid the player from resuming after a “game over” screen, or perhaps revert to the old restart-from-the-beginning game design model, in order to be truly winnable.

These days, to win a game is simply to see its ending, which may or may not be a happy one. No matter what the tone of the story’s outcome, though, to finish is to achieve a goal. This still does not equate to an objective win. This achievement can be considered a win based on the player’s personal desires and motivations, but is in no way definable as a win in the absence of any diametrically opposed loss. Proof of the subjectivity inherent to this “winning by finishing” concept is the alternative situation where a player may, in fact, triumph over a bad game by turning it off in the middle and never loading it into his or her console or PC ever again. In both cases the player’s desires are satisfied, but neither is a direct function of the game’s content.

To say that a player can beat a game is to assume that the game is doing everything in its power to prevent the player from succeeding. This is rarely the case outside of specific genres or multiplayer competition, which is no longer player vs. game at all. The intention of developers is almost always for the player to at some point see the game through to its end, regardless of challenges and obstacles along the way. There is no such thing as beating this sort of game because the game is not the enemy, and no victory can be won over it. In essence, the player is at all times working in synergy with a piece of software that is constructed so that he or she may extract enjoyment out of it; the game and the player are partners.

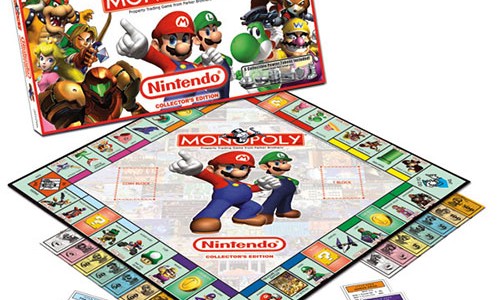

Some genres do emphasize winning more than others, and as the only games that can truly be won or lost should be considered differently. These are genres such as sports, fighting, racing, and strategy. These games do have definite and permanent win and loss states that cannot be altered once they have been attained. On the other hand, once narrative structure is infused, as is the growing trend in gaming, even these genres blur the concepts of winning and finishing. “Win” is essentially limited to those pieces of software that more closely approximate traditional board games, sports, or other such competition. Most other, story- or campaign-based games lean instead toward the realm of literature, theater, and film.

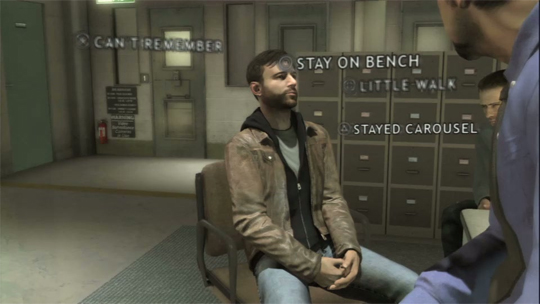

This natural lack of win and loss states toward which the video-game industry is progressing calls into question the definition and labeling of the industry as a whole. The evolution of the medium has made the term “video game” a misnomer. Much of what we manipulate on the screen is not a game at all, but a means to witness the expression of the dramatic arc. The recently released Heavy Rain makes this notion all the more obvious, clearly proclaiming to be “interactive drama” and abandoning the old “game” moniker. This directed experience gives the player control throughout, changing in key ways based upon player interaction, but inevitably concludes with one of a handful of predetermined denouements, each based on a single general outcome. Someone who plays Heavy Rain ends up acting more as a puppeteer than as contestant, completing a story rather than winning a game.

No matter what the label, the mechanics and structure of modern video games are changing. No longer are players asked to compete with a game in order to win, but are instead presented with narratives to explore and experience. Fortunately, each individual can choose to enjoy the type of play that he or she prefers, and even without actually winning, will come away with some measure of success.