Gamers hear the term “indie” quite frequently nowadays. With the advent of digital delivery and self-publication services such as XBLA, PSN, Steam, and other similar networks, independent developers have begun to work their way into the spotlight, the lion’s share of which normally goes to the likes of big men on campus like Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft, Ubisoft, Electronic Arts, Activision, and other “AAA” publishers. Last year even saw the release of a successful and well-executed documentary on the subject of independent games, entitled Indie Game: The Movie (you can watch it on Netflix).

But this wasn’t always the case. Independent games have elevated to center stage through developers’ hard work and dedication, and the efforts of organizations like IndieCade, an international independent games festival akin to the film industy’s Sundance. IndieCade is, in fact, the only standalone festival of its kind, the older Independent Games Festival (IGF) existing as a component of the annual Game Developers Conference. It is also open to the public, and in 2013, for the first time, has gone bi-coastal.

IndieCade East 2013, held at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image February 15-17, proved to be a natural extension of the festival, showcasing many of the recent IndieCade Official Selections, and offering a variety of panels and special events for attendees. Notable sessions included the Game Slam, hosted by Ouya (like a poetry slam, but with games), the PlayStation Mobile Game Jam, during which pre-selected teams worked on the show floor to build games for PlayStation Mobile over the course of the weekend, and the Iron Game Design Challenge, in which Parsons The New School for Design defeated New York University in an Iron Chef-like contest of game design.

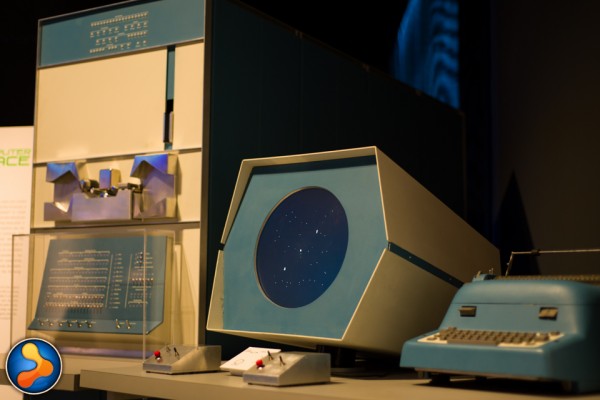

My favorite, The Spacewar! Decathalon, was a three-day competition across ten classic arcade machines standing like statues in a dimly lit hall one flight up from the rest of the festivities. The gauntlet was comprised of Asteroids, Battlezone, Computer Space, Defender, Galaxy Force II, Missile Command, Space Invaders, Space Wars, Star Wars, and Tempest, with the championship game, Spacewar! watching over the room, neatly tucked away in a corner on a working PDP-1 model. For a video game enthusiast, sitting in front of this behemoth was like staring into the face of God…and it was awesome.

The main reason for IndieCade’s existence, though, is to showcase the current gaming developments on offer from the creative and artistic minds hard at work on their personal masterpieces, in an effort to “create a public perception of games as rich, diverse, artistic, and culturally significant.” As I ventured around the festival floor, many titles caught my eye (and my grubby mitts), including a number of which that have already made names for themselves among on-the-pulse gamers.

I had never before had the opportunity to try Splice, the make-you-feel-like-a-genius puzzle game that Greg extolled in his review last summer. Sitting down at developer Cipher Prime’s demo station at IndieCade East began with fumbling and obscurity, but quickly transformed into a sense of rewarding challenge and achievement. Botanicula had escaped my grasp since its release last April, but this light point-and-click game of macro exploration and puzzle-solving turned out to be a meditative experience, even in the bustle of a games festival. And Dyad — well, I still haven’t played Dyad, which was released last July, but I looked on as gamers consistently went from confused and uncertain to enthralled and fully synchronized with the kaleidoscopic rhythm racing shooter. There’s clearly a level of understanding there that is unattainable without going hands-on with the game.

A little different, but oozing that “indie” street cred was a game I saw sprawled across a table, made of paper, and surrounded by four gamers and their dice. Armada D6, which appeared to have a learning curve more extensive than “sit down and play,” is a modular strategy board game about space colonization and ship combat, and is surprisingly elegant in its design. With six-sided dice placed on square tiles – each divided into eight peripheral spaces for movement, with a planet in the center – the attributes of each player’s fleet, from speed, to combat effectiveness, to colonization ability, were all laid out right there on the game board, for all eyes to see. Combat is as simple as a roll of the dice, and more advanced options can add depth to the core game. Most importantly, everyone sitting at the table was having fun, and the game’s creator has given something to the gaming community.

A higher-profile guest of IndieCade East 2013 stood quietly in a corner of the room, looking over the shoulders of those who chose to sit down and play his game.

Brendon Chung, developer of Gravity Bone and Nodie Award winner for Craziest Game of 2012 Thirty Flights of Loving, is a reserved and soft-spoken man. When I spoke to him about his short, independent titles, he described them as being built to elicit a variety of emotional states from players in comparatively short spans of time. He said there’s a big focus on overarching narrative in modern game development, and he wanted to instead distill his games down to the emotions players would feel while playing. I commented to Brendon that his game design fits that intention well – TFOL feeling drastically more disjointed than most games, comprised of a number of separate scenes spliced together – and he agreed that his level structure and emotional intention were inextricably linked during development.

I asked Brendon about the duration of his games and whether the reasoning behind their brevity (TFOL is 13 minutes long) was solely a result of his ambition to efficiently stimulate player emotion. His answer was that this approach was also due, in part, to him not having a surplus of time to work with – responsibilities consuming more of it as he’s gotten older. With a chuckle, I freely admitted that I always appreciate a short game, and as a player, Brendon is on the same page: offering the ability to enjoy games without a huge time investment has been a clear factor in his work.

Brendon is currently working on a new project that has been completely funded by the success of his first two titles: what he describes as a cyberpunk hacking game with a projected release window of “2013” and a very early and unofficial pricing estimate of $15. He stressed that he’s only “hoping” for a 2013 release, but he’s not on holding himself to any strict deadline. That’s part of the beauty of being indie: the game’s done when it’s done.

Brendon’s cyberpunk adventure will feature more traditional game design than his previous work, but one can tell that he’s still not ready to commit to conventionality. He told me that roughly 50% of this game will be confined to a hacking interface that will be accessed via a laptop inventory item carried by the protagonist. The other 50% of the mechanics will be a more familiar sort of world exploration.

“Oh, it’ll be different,” he said with a smirk, dispelling any doubt about his continued creativity.

They’re all pretty different at IndieCade, aren’t they? The developers, the games, and the fans who love them exude a retained sense of wonder about play that is often lost in the mainstream, heavily commercialized games market. It was a breath of fresh air to walk the halls of IndieCade East 2013, and I was reminded of the simple joys on which the industry is founded. I look forward to more.