The Stanley Parable feels like a conversation between player and developer. Illusions of choice and consequence are masterfully maintained, despite the very nature of the “story game” experience on offer.

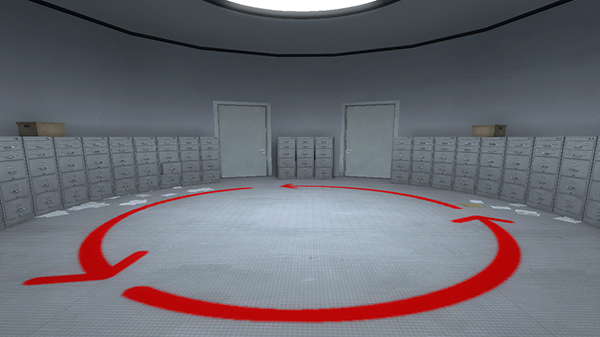

As in most video games, player agency upon the virtual world is limited at best in The Stanley Parable. Every aspect of the game is painstakingly scripted, and with each binary choice presented to the player, one path or another is discovered, leading to an ending that will never vary. Of course, the sheer number of endings built into the game create a sense of childlike wonder throughout the process of playing and re-playing. It’s inevitable that a person sitting down with The Stanley Parable will run through the brief and fickle tale two, three, five, ten, or more times just to see what else might have been in store for Stanley had he chosen to go through the left door instead of the right, or to take the stairs down instead of up.

If you’re curious, there are 19 “endings” (depending on what one considers a true ending point to a single run), and the game teases you to find them all.

Stanley is an office worker who spends his life mindlessly clicking buttons and responding to commands that come streaming to his computer terminal. His entire existence seems to be characterized by following instructions. One day, Stanley becomes conscious of an inexplicable emptiness in the building around him — everyone has vanished. So, at the urging of the game’s real star, The Narrator, Stanley steps out of his small, windowless office in search of answers…and The Stanley Parable begins.

The Narrator IS the conversation alluded to earlier, or at least one half of it. The Narrator describes to the player what happened that day: as you approach a set of doors, The Narrator calmly states, “Stanley took the door on the left.” Should the player agree to this narrative, the story continues through more halls, doors, stairwells, and other places I’d rather not spoil, right through to the end. The Narrator is happy, and Stanley is presumably happy.

The other half of the conversation, however, is the player’s obedience…or disobedience: the player’s willingness to do exactly what The Narrator suggests is the correct course of action. Should Stanley go against the prescribed story, The Narrator at first nudges gently to get him back on track, then becomes annoyed, and then speaks quite candidly to the player himself about the very fabric of the virtual reality they’re now exploring together. Depending on the chosen path, The Narrator may express worry, confusion, fear, confidence, pride, or a number of other emotions. He may choose to abruptly reset the game to Stanley’s office door, continuing his monologue from the previous run. The office may change in layout or design, new paths may open, and The Narrator may come up with new ideas to right his sinking ship. There’s never a dull moment here.

But why the word “parable” in the title? A parable is a short story that teaches a moral or spiritual lesson, so what is the lesson here? And this word is most frequently used in Biblical context, so how is that relevant to the content? The Stanley Parable comments, implicitly and explicitly, about storytelling in games, and control over the narrative arc. The religion in question is game design. We’re back to the conversation.

In The Stanley Parable, the participants are Stanley and The Narrator, but in reality, the give and take is between player and developer. The Narrator, like any good developer, has his story all planned out, and does his best to guide Stanley to the best possible ending. But Stanley, controlled by the player, is mostly free to do what he pleases once dropped into the game world. He’s free to do the unexpected, to disrupt the story, to break the game. Everything else is a contingency plan.

In The Stanley Parable, the participants are Stanley and The Narrator, but in reality, the give and take is between player and developer. The Narrator, like any good developer, has his story all planned out, and does his best to guide Stanley to the best possible ending. But Stanley, controlled by the player, is mostly free to do what he pleases once dropped into the game world. He’s free to do the unexpected, to disrupt the story, to break the game. Everything else is a contingency plan.

The Narrator scrambles to regain control time and time again, to redirect Stanley to some ultimate state of deliverance. Developers need to expect every unexpected player action and factor that into their design. The Narrator seems to do this on the fly, as if we’re peeking in on a play-test of an early game build, where chinks in the developmental armor are exposed and quickly patched up. In reality, however, developers control for these things in advance. No matter what the player does, he’s restricted to what the developer’s framework allows. Choice and consequence are illusions: each is just one of the options devised by the storytellers, no matter how novel it seems or how much control the player appears to have over the outcome.

The Stanley Parable has 19 endings, carefully crafted by developer Davey Wreden. It’s up to the player to find and experience them, not to create them.