Shank 2 can be described as “A sequel… with characters that… are in the game.” It can also be said that, “Shank 2 will… remind your… mom why she despises… video games.” More memorably, critics have hailed Shank 2 as “… developed…” and scorned it for “… blood…”

It must be frustrating to read dialogue so out of context, to know that whole chunks of content have been intentionally omitted, and to find “blood” the most descriptive element of an aged, repetitious entity. It must be equally frustrating, then, to learn that despite itself, participating in this affair is still as viciously enjoyable as ever, though the cost may be asking too much. It is engaging as a piece of off-color art, but then the ending disappoints, predictably.

Is the horse dead? Oh, he has been…

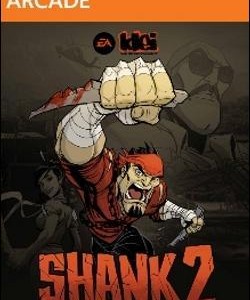

For gamers who remember arcade cabinets of Contra, Contra II, and Wild West Cowboys of Moo Mesa, the Shank series has been a guttural return to action side-scroller tradition. Simple controls, reactionary combat, and 20% gratuitous disemboweling established Klei Entertainment’s downloadable throwback as an evolved iteration of the genre’s classic hits, and a series to keep tabs on.

Shank 2 streamlines the mechanical processes of its comic-style murder origins, then shanks cooperative storytelling by replacing its predecessor’s successful two-player campaign with waves of goons. And in an effort to homogenize single-player, the ear-stabbing difficulty from Shank has been downgraded to chin-tapping challenges, infrequent and sometimes voluntary. To call it a step backward, though, would ignore the feral pleasure of scorching, decapitating, and otherwise disrespecting hordes of sub-human guns-for-hire.

It’s that appeal to the baser instincts that frames Shank 2, and the blood pool from which it draws its pulp personality. Whereas Shank followed the “Kill Bill” revenge murder recipe, the sequel borrows from “Salvador,” or the all-to-real violence of the Cuban Revolution, in its approach to a more conscience-driven homecoming plot. The weak-hearted president of a militaristic Latin state – Shank’s country of origin – kidnaps his people to find a suitable replacement heart, then strews these manacled refugees across a salty sea port, a wolf-ridden jungle, the husks of burning haciendas, and various industrial complexes. They are, as Shank might expect, well-guarded.

The narrative trajectory doesn’t share the intense direction of Shank writer Marianne Krawczyk’s (co-creator of God of War) first vengeance-fueled bloodletting, and motivation falls back on the classic, gamey bits for support. Undoubtedly by design, these ludic components received the better part of Klei Entertainment’s makeover attention. Shank shanks (and shoots, and grapples, and leaps, and chainsaws) with greater alacrity, and the re-mapping of the dodge function to the right stick and the interact function to a dedicated button release frustration from the control scheme. Timed counter-attacks also join the player’s arsenal, along with the odd environmental aid (deadly saw blades, sacks of fish, mounted machine guns), establishing a wider bevy of options for dealing with scores of henchmen, small, large, magical, and mammalian. Platforming is curbed to scarce usage, zeroing the intent clearly on Shank 2’s modified brawler combat, which is it’s true pleasure.

In some respect, limiting the design scope is admirable. Sure, each level will fall into the rabble-miniboss-rabble-boss formula, and fine-tuning the difficulty on Normal to a palatable balance might go unnoticed by newcomers to the series, but the care for these details is clear. From a macro perspective, it’s troubling to find unfilled space in Shank’s ambitious shoeprint.

The cooperative campaign, my favorite couple of hours from the first game, has been repurposed for Shank 2 into the now-popular “horde mode” mold, called Survival Mode here and imbued only with the ephemeral buoyancy of crusty bread. Perhaps that’s an over-understatement of its inherent value, as the rest of the campaign offers the same experience with scrolling backgrounds and cutscenes, but I can’t escape the need for narrative context to my organ grinding.

I blame, chiefly, the fantastic aesthetic direction in Shank 2 for my plot presupposition. Scott Pilgrim vs. The World: The Game identifies itself as homage to classic brawler games primarily through visual and audio cues, and the story matches by utilizing one of the oldest gaming tropes, “Your princess is in another castle.” With this knowledge, I enjoy the game for the raw play elements and, by in large, ignore Ramona Flower and her trysts with the seven bosses. The comic-art in Shank 2, in concert with the dramatic score and the overly dramatic voice acting, justify a deep and nuanced conversation between player and game. The actual product of the flimsy campaign narrative and an absent cooperative impetus seem farcical by comparison. Apparently, I’m just not getting the joke.

Eventually, I’ll return to Shank 2 for its tactile, reactive challenges. I’ve played half of the campaign on the Hard difficulty and it causes me to recognize what the game does well – forcing quick, tactical combat solutions out of the player in exchange for the gratification of achievement (not ‘chievos, just the regular kind, like in life). If the exchange were that simple, I’d forget the desire for something more complete in favor of a specialized experience in a diverse marketplace. However, Shank 2’s sin is not one of mundanity. Rather, it’s the lie of omission.