Knock-knock intrigues me, and I don’t know if it was ever meant to do anything more than that. I don’t even think it’s a “good game,” per se, and its introductory message tells me that it isn’t a game at all. Yet its nebulousness keeps me intent on exploring everything it presents, and even after finishing the game, I’m still not sure I fully comprehend its rules. Perhaps non-coincidentally, I find myself in a state of uncertainty vaguely reminiscent of the game’s protagonist.

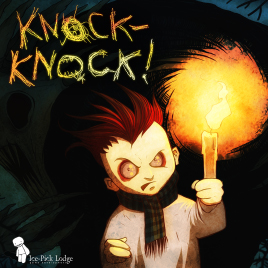

A bleary-eyed insomniac known only as “The Lodger” is trapped in a cycle of obsessive-compulsive nighttime wandering through his cavernous, ever-changing house and surrounding forest. Controlling this strange character, my actions are severely limited, and generally lack comprehensible feedback. As I tip-toe from room to room, anachronistic oil lantern in hand, my only options are to repair and operate the lights, open doors, hide, or wait — I do a lot of waiting. With all the freedom built into modern games, this simplicity is striking. And with the arguably excessive amount of guidance modern games provide, the fact that the consequences of my actions are unclear to me makes me noticeably uncomfortable. I’m in a consistent state of mild agitation throughout the entire experience.

I’m never actually afraid, though, partly because the game doesn’t dial up the horror and partly because my mind is occupied with other cognitive processes. I’m specifically uncomfortable with and attentive to the game’s mechanics; I don’t like not knowing the rules by which I’m playing, and I’m compelled to find out exactly what they are. Playing Knock-knock, then, becomes a compulsion, much like the somnambulistic, paranoid exploration of my weary, on-screen avatar.

I’m never actually afraid, though, partly because the game doesn’t dial up the horror and partly because my mind is occupied with other cognitive processes. I’m specifically uncomfortable with and attentive to the game’s mechanics; I don’t like not knowing the rules by which I’m playing, and I’m compelled to find out exactly what they are. Playing Knock-knock, then, becomes a compulsion, much like the somnambulistic, paranoid exploration of my weary, on-screen avatar.

Each night, I must shuffle around the house and survive until morning, but I can also escape into the gnarled, shadowy forest and amble on to the next evening whenever the front door opens. I have no idea when or why the door opens. I don’t trigger it; I only respond when it happens. Nightly terrors also seem to appear at random, seeking to harm The Lodger and I — two separate entities that begin to feel indistinguishable despite his frequent soliloquies directed squarely at the fourth wall. A clock on screen, strangely shaped like The Lodger’s face, counts down the minutes until dawn, and is dramatically rewound if these hobbling and floating specters make contact. They can even reset the night completely, sending me back to bed to wake up all over again. The creepy, disembodied voices that resonate through the house keep me alert to these imminent dangers.

Knock-knock’s sound design is perhaps its single most laudable component. Slamming doors, cracks of lightning, bursting light bulbs, howling wind, despondent sobbing, mysterious thumping, aggressive banging, and other startling noises cut into the still silence of the night, and ghostly voices — male, female, and… other — address me from all directions. What slack the simple, cartoonish visual presentation leaves in its expression of horror, the audio department zealously picks up and runs with.

Knock-knock’s sound design is perhaps its single most laudable component. Slamming doors, cracks of lightning, bursting light bulbs, howling wind, despondent sobbing, mysterious thumping, aggressive banging, and other startling noises cut into the still silence of the night, and ghostly voices — male, female, and… other — address me from all directions. What slack the simple, cartoonish visual presentation leaves in its expression of horror, the audio department zealously picks up and runs with.

But there is really nowhere to run to. Although time becomes more significant thanks to a limit placed on the latter half of the game (which can easily trap players in an inescapable game-over situation only remedied by starting from scratch, by the way), Knock-knock‘s hooks are defined early and never embellished. I’m less compelled to continue playing by the game’s nominal narrative than by the urge to figure out the systems by which the whole experience operates. It’s not a question of, “What’s through that door?” It’s a question of, “Why the HECK does that door open like that?” I may have, at some point early on, felt immersed in the obscurity, but by the end of the game I’ve grown as weary as the sleepless Lodger — a guy who does nothing but walk around turning lights on and off.

I remain intrigued, but I’d rather just go to sleep and forget about it.