A few hours into Inversion, a group of boorish soldiers, grizzled and uninspired, wonder about the mysterious enemy. Aside from a few unintelligible grunts, the only distinguishing characteristic of the opposing creatures are their advanced weaponry and a collective desire to be Wez from Road Warrior. Eventually, the leader of the soldiers tells them to pipe down with all their jib-jabbin’.

“Last time I checked, none of you are professors, so quit theorizing,” growls the commander. “We only got one job: blast these [lovely gents] back to wherever they came from.”

In those two articulate, terse sentences lie the problems of Inversion. Usual, tired problems.

Inversion begins like anything else – with motivation. However, since our t-shirted hero is about as likable as another post-apocalyptic setting, the motivation that pushes the story feels translucent. It’s a thin thread about a lost daughter and going through Hell and back to find her. It’s loving but weightless, perhaps an accidental motif for the game’s selling point. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Davis (t-shirt hero) and his cop buddy are taken prisoner by a rogue army arisen from the ground called the Lutadores. The Mexican wrestler mutants give the two men devices that can manipulate gravity so that they can mine for coal or something. Failing to see the obvious flaws in their trust barriers, a lot of Lutadores are killed as Davis and friend escape with shiny new toys.

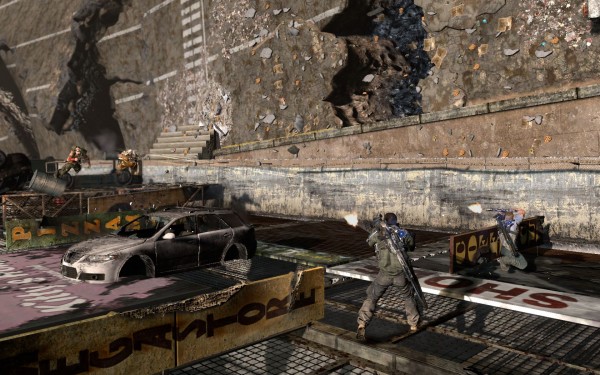

The main driving force behind the game and its platforming are these devices. With them, players are given a limited amount of power that can either levitate objects and enemies – lifting and exposing them from cover, ripe for a tossing or showering with bullets – or suppress enemies – pinning them to the ground, sometimes with enough power to dismember. The problem is consistency. Getting the right aim with the weapon is tedious, as enemies often seem immune unless hit directly. In the end, the mechanic is more about learning when to use it at the right moments, against the appropriate enemies, rather than spamming it.

It takes time to get the wheels turning, but about halfway through the campaign I started enjoying myself. I strategized. I practiced and remembered patterns. The laborious feel of the game was tiring, but learning enemies and utilizing the power correctly had me engaged. Still, I continued to have trouble immersing myself in each new mission. I dreaded the unwieldy zero-gravity moments, with clunky tracking similar to the wired Matrix fights. I groaned at the futile characterization. The cover mechanics played like pushing opposing magnets together. There’s plenty to dislike. There’s plenty to have to trudge through in order to unearth the gleaming moments, but they do exist.

Like when I battled Darksied an armored Lutadore boss. His stringy peons rushed from left and right, strapped with bombs and shovels. Shields broken, my inversion powers suspended enemies aloft, tossing their corpses into one another, pinning them down with secondary capabilities. The head Lutadore charged with an electrified whip, so I rolled to cover, popped up, scurried to regain health, lifted cars and hurled them at mechanized enemies, swapped shotgun for rocket launcher for grenade for special power. Enemies advanced, advanced, advanced.

Throughout my playtime, I spent a good portion imagining what Inversion could have been. What if, by some glorious circumstance, Namco Bandai and Saber Interactive took a different path. They chose a story full of inspired characters and colorful palettes. My version of Inversion wouldn’t fall prey to the third-person shooter checklist. It wouldn’t be Gears of War: Lite. It would question our grip on our own reality (like the current incarnation unsuccessfully tries to do) alluding to the mechanics as something more than just a gimmick. What if you lost all that you loved in the world? How much of yourself would you lose? Like Outland or maybe even Braid, Inversion could have wed gameplay with a message. It could have been a riptide.

Instead it’s a shallow twist ending, unsettled and dim. I applaud ending irresolutely, but Inversion misses when trying to hit on something more meaningful. By the time the end rolls around, my brain is already switched off. I’m just following orders.