As the longest console generation in history comes to a close, the GamerNode staff reflects on the games that made this era so great. Games of the Generation is a new GamerNode original feature that allows us to share that passion and nostalgia for the most memorable and significant titles of the last eight years — since November 22, 2005, specifically — and explain why these games have defined a generation and will forever stand as touchstones in gaming history.

August 21, 2007 – Irrational Games – 2K Games – 360, PS3, PC, Mac

BioShock

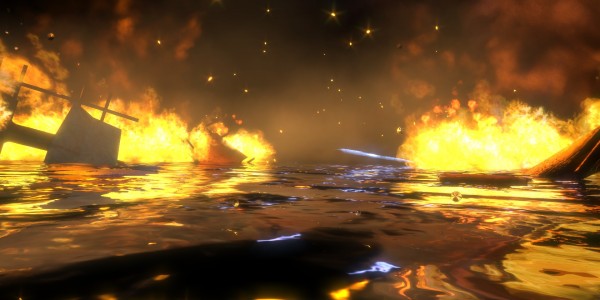

I started BioShock again earlier today, on a Windows 8 machine decked out with high-end gaming hardware, and it did not work.

The sound, for one, would not play. I watched the still-smoking shell of the airplane ignite before me, the water textures gleaming and wet — wetter than I remember. I sat through the silent slideshow from the desk of Andrew Ryan, and quoted the lines to myself. “No, says the man in Moscow. It belongs to everyone.”

The animations weren’t timed correctly either. My bathysphere emerged to see two frozen figures, one barely visible save for two glowing hooks, the other waiting for the almighty hand of code to drop. Eventually it did, and he perished just the same, as rehearsed.

I discovered subtitle options to fill the empty aural space visually, and it ended up being as bad an idea as you’d imagine. The Art is subtitled “Art”, and so on.

I googled the technical failing, quickly finding a post with a number of potential fixes for my issue. Yes, stereo audio is enabled. Yes, I have permissions to run the file. Yes, I’ve installed BioShock on my machine.

The actual fix for the broken animations and audio was to open the file directory where bioshock.exe resides and change the properties of the file. Particularly, to run bioshock.exe in Compatibility Mode for Windows XP (Service Pack 3).

Isn’t that BioShock? To dive into the minutae that defined an era and pull out some concept, some sensibility that is not only offensive to modern culture but is, taken to an extreme in human nature, horrific? To look into an aged reflection and see it spit back? Then bullets and magic hands?

I didn’t need to lose the audio to appreciate what Irrational had achieved in BioShock‘s soundscape, but the recurring portraits popping into the radio at the lower corner were a stark reminder. To say nothing of the world-building and level design (I will), the voice-acted performances were and still are a revelation in game development.

Take, for example, a short sample of the voice acting from Singularity, a game that was released three years after BioShock and still underbid it in concept and execution. Generic military-speak and Russian rrrrrrr’s? The dying scientist could just as easily be at the dentist.

Now listen to these: Sullivan’s interrogation, Ryan’s Ecclesiastical diatribe, Martin Finnegan’s threat

The subtleties speak, I believe, for themselves. And that’s without any mention of Karl Hanover’s work at Atlas, or Greg Baldwin’s Fontaine lilts.

I’ve written before about BioShock’s individual character triumphs, and I could write six more. The commentary on the madness of the artist’s lens in Sander Cohen, or the ethical dilemma of science played out between Dr. Suchong and Tenenbaum. Or the powerful mythos of gang leaders in Fontaine, or the sinful secrets of lust in pairing Jasmine Jolene with Diane McLintock. Even Bill McDonagh’s quiet internal rebellion has meat on its bones.

These personalities are emblematic of the ideas they wrestle and the space their voices fill. When BioShock first came out in 2007, reviews praised its “non-linear” level design and “atmosphere,” both of which are laudable, though symptomatic. The devil, as they say, is in well-placed 3D models and textures.

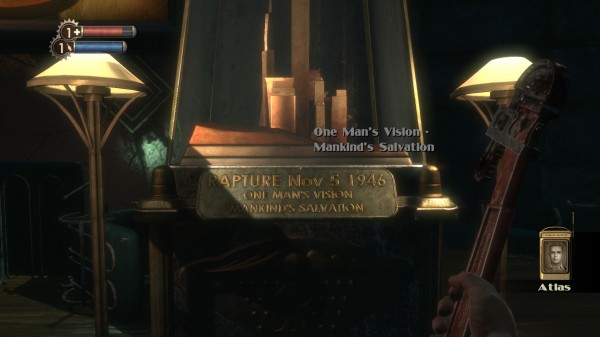

That is, the character of Rapture is a collection of details rather than one larger concept. The now-overwrought conversation on Randian objectivism is just an essay without the supporting structures; literally, the pieces that hold Rapture together.

Just look at the lobby in Fort Frolic.

Upon entry, the space explodes with potential. Not only are there four distinct pathways out from the lobby, but the potential for discovering all the details: for scouring for illuminating bits of architecture, discarded bodies, and those glittering bulbs of narrative expressions, the audio diaries. And notice the locked prize cases, only accessible upon returning to Fort Frolic late in the game.

What Fort Frolic does best is calcify BioShock’s theatricality in character and place. Or, as Cohen puts it, “Life. Death. The burden of the artist is to capture.”

With Creative Director Ken Levine’s background in theater, it’s no wonder that BioShock became the stage play that it is. Kyle Fitzpatrick may be the only actual character to alight a stage, but the careful level design has the pen of a scriptwriter all over it. Take the Saturnine caves in Arcadia, or Atlas’ just-out-of-reach tragedy in the Fisheries, or (my favorite) the dentist’s office in the Medical Wing or weapon upgrade basement in Fort Frolic. Theater is a conversation, and horror games come as close to that kind of playful parley as any game genre.

And then there’s the epiphany.

So much goodness has already been written on the twist that gobsmacked my college freshman face, with Clint Hocking’s take squarely in the lead. Without adding a voice to that cacophony, I’ll reveal that I have on three different occasions shown that segment to folks who have never played the game, and in each instance they have been both transfixed and confused. Confused, I believe, because they assumed as I once did that this kind of narrative trickery, launching into meta-narrative trickery, only existed in the realm of capital-L Literature and The Usual Suspects. Hooray for watershed moments.

To be clear, I understand it’s pulled directly from System Shock 2, which I didn’t play until several years after I played BioShock, which is in several concrete ways much more enjoyable that System Shock 2. The point is not that it was first, but that it was the first for me. And so Rapture’s secrets will always be that way in my memory.

Then, to pack the aesthetic and narrative feast into a first-person RPG shooter… the demand itself is astounding, though rightly table stakes in modern game development. I appreciate the supposed moral tension of the Little Sister “decision,” but it comes down to an economy, and economically it makes sense to be amoral. That is, the best combination involves saving and harvesting Little Sisters.

The invention of the Big Daddy is the real innovation in BioShock, and one that came conceptually early in its development. The Little Sister is really just a reward mechanic counter-weighting the risk to approach and fight a Big Daddy, who thankfully evolve throughout the game, and work in tandem with so many of the game’s other systems (security, plasmids, splicers) that each altercation becomes organic where it would otherwise be a grind. BioShock’s pacing desperately needs the peaks afforded by the Big Daddies, particularly when paired with the sometimes overwhelming amount of time spent in the quiet, tedious hacking tube game.

If it weren’t for that last third of the game, and the gut-buster of a “good ending,” and the mountains of violent murders the player must climb to that morally just reward, BioShock might find itself as the objectivist despot of a console generation. For me, there will never be choice.

are you going to do an Games of the Generation article about TLOU too ?

thiis game is one of the best games i have played in my life

great article though