Welcome to another round of GamerNode’s new ongoing column, Counterpoint.

coun·ter·point n \kaūn-tər-pōint\

1. The technique of combining two or more melodic lines in such a way that they establish a harmonic relationship while retaining their linear individuality.

2. A contrasting but parallel element, item, or theme.

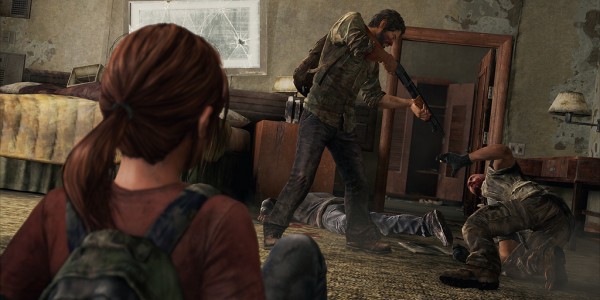

This time around, the Node crew will be discussing violence in video games and how it’s perceived. Naughty Dog’s upcoming new post-apocalyptic IP, The Last of Us, has been praised by multiple outlets for its mature take on violence in games. Some believe the game will support a strong enough argument that it may even change common views of violence in video games. One opinion Dan quoted even suggests that the game will be “a realignment of gaming’s moral compass.”

Well, there is debate among us Nodees on the validity of that opinion, so we turn again to Counterpoint. Can violent games deliver a satisfying gameplay experience while decrying their very core element, i.e. violence? Or will The Last of Us help turn the tide of how gamers dissect and internalize their experiences with this often brutal medium?

Dan’s Stance – “Having Your Pacifist Cake and Eating Shotgun Cake Too”

Ben Kuchera of the Penny Arcade Report writes:

“The Last of Us seems to have bypassed this argument (the tension between the characters and the video game gunplay) entirely due to a setting where violence is a given, and Naughty Dog has filled that setting with richly drawn characters. The dissonance has been removed, or at least the setting and characters were built with the idea that it could be ameloriated. The Last of Us features characters that, based on what I’ve seen, act the same during the cut scenes and the action segments.”

If we were talking about a movie, I’d agree. It’s clear that Naughty Dog is taking a more mature approach to violent encounters in post-apocalyptia, side-stepping the hyperbolic silliness of Fallout 3‘s VATS gore or RAGE‘s overt self-awareness for something more likely, more grounded. The relationship between protagonist Joel and child cohort Ellie looks like it’s driving that dynamic, which is the kind of character-driven plot gaming has had so little of (Enslaved would be another example).

Now THE BUT. Buuuuuuuuuuuut, this is a video game, not a movie, the key difference being interactivity. In static media, a character is entirely committed, by the author for the viewer, to the predetermined choices, violent or otherwise. Violence may be portrayed through a first-person lens and still be instructive, in some cases disturbing. The main character in a shooter film called Rampage (forgive the obscure example) murders a town full of innocent bystanders in full body armor and without remorse. At no point while watching this movie do I feel any satisfaction in his serial killing. I’m made to identify with his character (he is the protagonist), but not the violence.

The Last of Us is a survival shooter. According to its mechanical construction, players will be urged to kill. The lives are just as fictional, and the body count is about the same, if not higher. Kuchera (and others) have made the argument that the character and story context makes Joel’s serial murders more poignant, even going so far as to say that the game carries an anti-violent message. I submit that it cannot, because the player pulls the trigger, not the developer.

Shooting games are propelled by the pleasure of aiming and shooting. I’m not going to pretend to understand the psychology behind it, and will stick to just asserting that, from personal experience, I know that tactile satisfaction. Throw whatever wrapper you want on the target or on the gun, that principle holds true.

Based on that, I’d argue that any game which employs point-and-shoot gameplay as a pillar of the experience can’t convince me that the actions keeping me involved in the game are morally or practically incorrect. To give that context, I can’t see a typical American 20-something male blowing the lid clean off their first digital stranger in The Last of Us, then putting the controller down out of sudden conviction about the impropriety of violent media.

I guess it’s just the question of having your pacifist cake and eating shotgun cake, too.

And just to preempt the obvious response, no, I don’t care about Ellie’s early childhood or Joel’s experience on “both sides” of the fence. My argument is based on the idea that these essentially aesthetic ornaments are undercut by the more powerful element of play that sells the game and defines the experience. Sympathy for a scripted character matters less than a virtualized sense of self-preservation.

Mike’s Stance – “The Fact That I’m the One Doling Out This Violence Makes Me Even More Repulsed”

While a virtualized sense of self-preservation may overcome any sympathy or grief I feel for characters, that should by no means mean that I’m satisfied with pulling the trigger.It’s obvious that I want to beat the game that I am playing, that I don’t want my protagonist that I control to die. In order to survive I’ll kill those who are in my way, but does that mean I have to be happy with the outcome? Just because I’m pulling the trigger I’m some psychotic freak who gets a sick sense of satisfaction from virtual murder? Even as the people I kill plead mercy?

To put it in the context of The Last of Us as you did Dan, I’ll refer to my experience with the on-stage E3 demo for the game. As Joel slaughtered those looters around him, we really didn’t know just who those looters were and whether or not they were really bad people. They begged for their lives, felt sorrow and anger over their deceased companions, and struggled like they were afraid, not cocky and arrogant like most antagonists in a video game. All the while, Ellie is expressing disgust right in your ear as you inhumanely silence these unfortunate souls for good. I don’t know about you, but those situations are going to make me hate violence. It isn’t glorified like in your typical military shooter. It’s grounded in reality and we’re shown its ugly side. It may be necessary, but I felt horrible for the people Joel killed.

As I said in my preview on that same demo:

“I feel shame. I feel guilt. I certainly don’t feel like the hero I’ve been in all games I’ve played before this. Instead I feel like someone quite different. I feel like the villain. But despite all of that, despite how wrong it all felt, it got the job done and kept Ellie safe, making it feel at least a shade of right. That’s the horrible duality of survival; the convergence of black and white into something grey and dirty.” This is the anti-violence message that The Last of Us is trying to make. It feels right only because it’s necessary for survival, and that actually makes it feel even more dirty. If anything, I think that the fact I’m the one doling out this violence makes me even more repulsed. Will it stop me from shooting people in Halo or Battlefield? No. But will it make me respect life and look down on violence in every day life? You better believe it.

Eddie’s Stance – “Repulsion Arises from the Greater Level of Agency”

While I find the initial quote citing “a setting where violence is a given” to be ridiculous and irrelevant to any discussion worth having (violence is a given in the settings of just about every game on the market, duh), I do feel that it’s possible for a game to present violence in an effort to disgust the audience, whether they are interacting with that violence or not. Even in static media, the audience is guilty of participation, to a degree, by simply allowing the story to continue; whether it’s in a book that can be closed or a movie that can be turned off, the act of observation is what brings the fiction to life in the mind.

In games, I would argue that the repulsion arises from the greater level of agency, rather than the authored, unchangeable elements of the story. A game can create situations that urge a player to act violently, but simultaneously suggest that these behaviors are morally unacceptable, introducing a sense of shame or regret in the player for following through. I would argue that this causes many players to dissociate themselves from the game’s protagonist, despite having been the sole cause of those characters’ wrongdoings when it came time to act. Viewing the game, then, as an authored work completely out of the player’s control, really diminishes the effect of that violence; it’s reconciled as something more static than just a game.

It’s worked for me before in games. Manhunt 2, which had me seriously questioning my commitment to participate in its grisly activities, comes to mind, and we all recently read Greg Galiffa’s review of Spec Ops (do yourself a favor and do that now if you haven’t), which packed some potent thought-food between its bang-bang, stab-stab.

As for The Last of Us, its hard to tell at this point. Maybe it will work and maybe it’ll be all hype and no delivery, as games sometimes are. As far as a “realignment of gaming’s moral compass” goes, I doubt that assertion will hold water in the end.

Dan’s Rebuttal

In a direct response to Eddie, and in the tradition of “ways douchebags answer questions with questions”, how did you respond to “No Russian” in Modern Warfare 2? I think the answer there must be a personal one, and would help to explain whether or not a person can be repulsed in the midst of tactile satisfaction, or if the two are mutually exclusive or inclusive.

And in direct response to Mike, I’m making the argument that the feelings you are asserting are based on the “movie parts” of the game, for lack of a better term. We’re made to identify with Joel an Ellie as protagonists. We are made gleeful serial killers by a controller in our hands and an avatar on the screen.

Eddie’s Reply

I failed to pull the trigger on the innocents in “No Russian.”

I was, however, playing what many might call a “lawful good” character in MW2. (And some might say that an FPS like this makes a player embody the protagonist.) In games where I create a character myself, from tabletop RPGs to any BioWare title, I have absolutely no trouble making the most heinous asshole anti-hero and mercilessly destroying anyone and everyone who blinks the wrong way. Do I author that RPG character, or do I embody him, like in MW2? Which will I be doing in The Last of Us?

Mike’s Reply

Well, in the E3 demo everything that happened was part of the action. It was all going on as you were shooting your guns at the enemy and acting as the avatar, not as a spectator watching a cutscene. That’s what’s giving the violence context in the moment and making you feel the weight of every squeeze of the trigger.

Unless you’re arguing that you just ignore the context and feel great regardless because of the mere action and that it isn’t real. In that case, perhaps it’s a matter of opinion. Whenever I play a game, I suspend my disbelief and try to believe it’s real; that every kill I collect is silencing a life forever. With that line of thinking, it’s easy to see how context or “movie parts” of a game will affect the number of times I pull a trigger or how I feel when I do it.

This actually plays perfectly into your point to Eddie about “No Russian.” I personally was mortified and disgusted by the act that was happening on screen when I played through it and couldn’t bring myself to pull the trigger on innocents, even though they weren’t real and shooting them would have helped my avatar keep his cover. My morals and shock wouldn’t just allow me to.

Greg’s Stance – “It’s Possible That Analytic Conversation Will Flourish”

“I can’t see a typical American 20-something male blowing the lid clean off their first digital stranger in The Last of Us, then putting the controller down out of sudden conviction about the impropriety of violent media.”

Maybe it wouldn’t happen to that exact effect, but I do believe a game can make an American 20-something male reflect on and consider his actions throughout his experience. When the “No Russian” debacle was first brought up, it touched upon this type of result. However, that’s not a fair example since you had to play it the way it was scripted. As you point out Dan, it falls under an authored experience like a movie.

Still, it was an interesting shift – to me anyway – in the dialogue about violence in games. Here was a military shooter wherein copious amounts of dead soldiers are splayed across screens on a global scale. And here comes a mission that forces players to commit an act of terrorism. Shock value? Sure. But poignant nonetheless. That moment left people uncomfortable. It left them analyzing and discussing.

At this point in the game, that’s the result I hope for with this topic. Like Mike, I paste my views and thoughts in my actions in games. I mentioned in my Spec Ops: The Line review that the violence is ordinary and that bothered me. Having a gun and shooting thousands of digitized people is nothing new for games, but a game holding a mirror up to me and making me realize how obsessive and thoughtless I become when doing so is layered, intelligent and frightening.

And with a game like The Last of Us, an experience that will presumably illustrate violence as deplorable but necessary, it’s possible that analytic conversation will flourish. As proven by the E3 demo coverage, people are already dissecting the game’s themes. Here’s hoping that evolves into something affirming and influential. Or it won’t. Maybe the game will have a lotta Uncharted‘s pew-pew, bang-bang under the cover of melodramatic drapes. I’m praying for the former.