Herman Webster Mudgett, better known by the alias H. H. Holmes, confessed to the murder of twenty-seven individuals in the Chicago area before, during, and after the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. As detailed in Erik Larson’s non-fiction account of the event, The Devil in the White City, Mudgett lured his victims, many of them married women, with a perverse charm and handsomeness amplified by his emotive blue eyes. Of his documented quarry, none suspected they would be murdered and their bodies sold for experiments, and just two blocks from the greatest scientific and artistic spectacle to date.

"BioShock has always been about unintended consequences," says Irrational Games’ Creative Director Ken Levine. Players who plunged into the underwater city of Rapture in the original BioShock were duped by a con man, a distinctly memorable moment that encapsulates the game’s narrative and ludonarrative (a term coined by Clint Hocking in his critique of BioShock‘s thematic entity). As I look to Irrational Games’ sequel, BioShock Infinite (BioShock 2 was developed by 2K Marin), my guard is up. No murderer or con man will befool me this time… I’m sure.

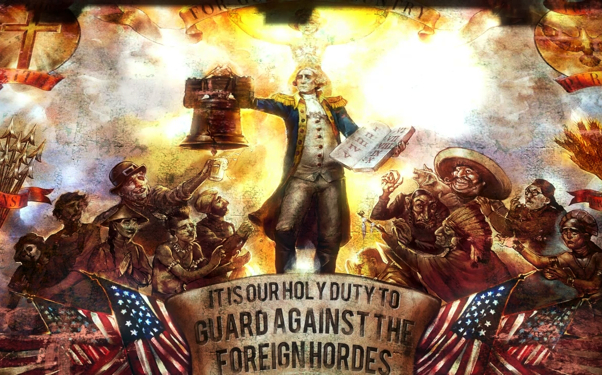

So to lull the gaming public and — clearly — me, Levine and team assembled a second gameplay demonstration for E3 this year, unveiling tears, skylines, and player choices (though I’ve been warned of "choices" before) in considerable depth. Columbia, the floating city-weapon and setting for BioShock Infinite, breathes almost organically against a bright blue backdrop. In subtle ways, it’s a spiritual opposite of Rapture; rather than a triumph of science and the individual, it’s an architectural, artistic piece de resistance inspired by national pride. The buildings heave in precarious rhythm with the sky as the camera focuses on its prey.

Protagonist Booker DeWitt, player-character and fully-voiced pragmatist, explores Notion’s Sundries and Novelties for loot (a mainstay activity in atmospheric games and RPGs) while his bounty, the recently rescued Elizabeth, marvels at knick-knacks of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. "Booker! Booker! Look, gold!" she says. "That’s gold like I’m the king of England," he replies. It is still early in their relationship (about one-third through the game), and Booker’s words carry no affection.

Upon finding a Bucking Bronco tonic and some loose change, the emptiness of the colorful store becomes apparent. A dirty mattress on the floor, an eerie silence, and the out-of-place normalcy of items neatly arranged on the shelves disturb an otherwise light-hearted moment. Then Songbird’s metallic call rings through the air as he lands with a crash nearby. Elizabeth sobs, "No, no, no, no!" while she and Booker take cover behind a display case. An ominous orange light pours into the window from one of Songbird’s giant eyes; he is searching for her. The light turns to green, and he flies away. Shaken, Elizabeth takes Booker’s hand.

"Promise me," Elizabeth says.

"I will stop him," Booker says.

"No, that is an oath you cannot keep. Promise me that if it comes to it," and she brings Booker’s hand around her throat, "you will not let him take me back."

"It won’t come to that, alright?"

This moment reminds me of that first Big Daddy encounter in BioShock. At first, fear, then a gathering of strength. Finally, a moral qualm. Songbird’s relationship with Elizabeth is complex. He’s her probation officer, keeping her in Columbia against her will, but the only creature she has ever known until Booker. The Songbird’s origin and motivation is unclear.

The human pair cautiously exits the sundries shop, and Elizabeth runs ahead, singing and calling to Booker. Her childlike optimism foils Booker’s macho, jaded heroism. She kneels over a dying horse. "He’s in pain," she says. "Not for long," says Booker. It’s an expected reply as he takes out his pistol, giving the player a quick execute option similar to the renegade and paragon moments in Mass Effect 2. She catches him before he can pull the trigger. "Wait, wait… there’s a tear! I can control it this time," she says.

Explanation is warranted, here, as "tears" seem to be the "Nano Forge" of BioShock Infinite (or perhaps "StarGates" are a more familiar reference than the weapon from Red Faction: Guerilla). Everyone in Columbia can see these tears — note the disappearing banner in the first gameplay trailer — but only Elizabeth can manipulate them, making her a prized object for any power-hungry faction. These are literally dimensional tears, glimpses into other worlds, other possibilities and choices.

In the instance with the horse, Elizabeth begins to conjure the equine back to health by replacing it with a healthy horse (or healthy horse parts — ew) but loses control of the tear, sending her, Booker, and the horse onto a street corner in what appears to be 1983. A movie theater marquee reads "Revenge of the Jedi" — the almost-title for Star Wars VI — and streetlights illuminate the rainy streets. An ambulance hurtles towards the trio, but vanishes just as Elizabeth manages to close the tear and fall back in exasperation. In this moment, I’m glad Booker didn’t shoot the horse.

BioShock‘s ludonarrative delivered a pessimistic and honest message about the video game medium. The tears serve a parallel function in Infinite. Like games, tears offer a glimpse into another world, in whatever time or place, and one that isn’t entirely under the developer’s control due to player agency. Games retain poignancy — as any game critic would be well advised to argue — in the physical world, particularly from a psychological standpoint. Wielders of the tears like Elizabeth (developers) bring outsiders (like Booker) into alternate dimensions (their imaginations), for better or worse. Experienced wielders deliver a more controlled experience. And as many wielders will attest, relationships with publishers can be, at times, a form of imprisonment. Likely, Irrational will provide a value judgment on the creation and manipulation of games (or any art) that will come with the narrative, but for now, speculation reigns.

As Booker and Elizabeth continue, the player receives a choice to head forward or to restock. Booker chooses the latter. The goal is to reach Comstock House, the residence of Columbian founder Z. H. Comstock and a stronghold for the Founders, a gentry faction based on the ideals of American exceptionalism. In between Booker, Elizabeth, and the nativists seeking to imprison Elizabeth back in her tower are the Vox Populi, the political antithesis of the Founders. Booker approaches the area cautiously, knowing that the Vox Populi are wild and dangerous, seeking only to destroy Columbia (and Elizabeth with it) in the name of "the people", a kind of perverted Marxism.

After remaining an inconspicuous observer to Populi violence riddling the streets — though involvement, Levine says, is up to the player — Booker stumbles on a public confession. A postman, frightened and coerced, says, "I confess that I am an agent and provocateur of the Comstock regime. I was responsible for the 1904 Emporium bombing. I was the mastermind …" His admission is cut short as Booker activates a timed option to vocally intervene. "Hey, he’s just a postman. He didn’t hurt anybody," Booker yells to the crowd.

Despite a decidedly Ghandi-esque approach in the vernacular of video game approaches (this is just one of multiple ways to handle this encounter), the Vox Populi identify Booker and begin the assault. Cue skyrails, the palpably exciting movement augmenters that allow Booker to engage in vertical combat, both on-rails and off. He takes a short ride up to a platform where he dispatches a few Vox gunners with a blunderbuss-style shotgun. A group of melee enemies swarm him from the flank, and he uses a levitation tonic power to suspend the enemies, then calls to Elizabeth for support. She opens a tear for a skyrail crate which smashes the floating Vox out of the sky.

A zeppelin appears, appropriated for Vox use by splaying angered messages across its starboard — "WE WILL BE HEARD." Booker races to the nearest skyrail, ascending the vertically integrated square by hopping between rails, dodging enemies and crates. One jump does not find a parallel rail, and Booker freefalls, arms flailing, vision blurring, velocity increasing. Building stories below the last rail, he connects with a mercifully placed rail that leads him to the heavily armed, rocket-spraying blimp.

After dispatching the enemies on the deck, again combining shotgun skills and the levitation power, he enters the belly of the floating beast, where a group of Vox protects a glowing red engine. If I’ve played any shooters this generation, I’d bet it’s explosive. And so it is, as Booker lands a few shots on the manifold, the zeppelin erupting into fiery explosions. He makes a tear (not that kind) for the exit and doesn’t hesitate with a leap of faith, once again plummeting at increasing speeds towards the square below. At what seems like the last moment, Booker’s skyhook connects with a rail, delivering him to the safety of the pavement. "Booker, that was amazing!" Elizabeth says, breathlessly. Her feelings mirror my own.

The celebration ends as Songbird crashes to the ground, swiping Booker into a nearby building. His screeching shakes the ground and he approaches the protagonist, ready to stab sharp appendages down on the now powerless Booker. Elizabeth intervenes, standing between the two adversaries. "I’m sorry! I’m sorry," she pleads. "I never should have left. I never should have left. Take me back. Take me home. Please." Songbird’s eyes change from menacing red to green as he grabs Elizabeth and takes flight. Booker lunges out of a splintered wall, connecting with a skyrail, hot on the trail of the princess to another castle.

As I step blinking from the demo room, I am, to put it plainly, surprised — exactly what I couldn’t be; I played BioShock. I was ready for the twists, for the straining political ideologies and sci-fi powers Infinite will no doubt employ. Irrational meekly reminds me that I couldn’t be less prepared.