In his effort to glorify games as a viable story-telling instrument, Quantic Dream developer and director David Cage has said games need to grow up. He’s advocated more narrative, emotional structures in order to break out of the game industry’s “Peter Pan Syndrome.” He’s named-dropped games such as Brothers: A Tale of Sons, Unfinished Swan, Gone Home, and Papo y Yo for having a soul. In an interview with Tribecafilm, he described the current state of the medium as “meaningless.” In that same interview, he went on to say how games are ready to create something that “like films, can change the world, or at least try to.”

Cage’s thoughts on the culture aren’t anything new. He’s told us plenty. With the release of Beyond: Two Souls he’s had a chance to show.

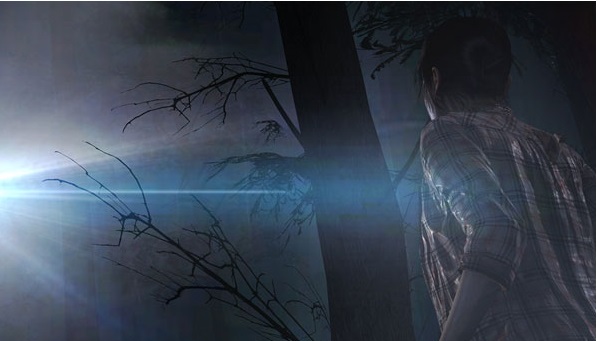

Put simply, Beyond is a series of interactive quick-time events centered around Jodie, played by Ellen Page, who is a reclusive teen with supernatural abilities granted by a spirit named Aiden that is physically tethered to her. The story starts small, introducing the scientists researching and testing a young Jodie. These scientists, the primary played by an expert Willem Dafoe, serve as parents and companions to Jodie.

Her real parents are a mystery; her foster family gives her up after becoming increasingly frightened by her gifts. Jodie is alone. She trusts very few people. Aiden burdens her life as much as he empowers it. Without really knowing anything about Beyond going in, I thought the experience would stay here, in this intimate space with a confused teen and her extraordinary abilities.

Instead, it goes somewhere else, and the controls, the style, and the story are forced to awkwardly follow.

Cage has pointed out in an interview with GameSpot that Quantic Dream’s challenge with Beyond was convincing its larger community of players, now piqued by Heavy Rain, that their newest project is worth the time. Some of these players, he said, are interested in games about “shooting and about action, killing, competing and adrenaline.” But Cage wanted them to consider Jodie, who is admittedly a gun-less heroine, and see if they still appreciate her story. So he gave Jodie a gun.

I see his point, but the issue remains that Beyond reaches for branches that are under-grown and weak. It incorporates big set pieces and cover systems. It fuels itself with a disjointed story that hops from time frame to time frame, leaving me to wonder, “just who the hell are these people Jodie works with?” It creates a narrative that doesn’t justify its own splintered structure.

Jodie moves from angsty teen to CIA operative to fugitive in rapid succession. During her military stint, she combats hostile factions of a militia that’s never fully fleshed-out. She’s surrounded by high-ranking U.S. military archetypes, shallow and underdeveloped men commanding her to do what they say. She sometimes seems grossly untrained and uninformed for the missions assigned to her. She stumbles into grand, spiritual mysteries that are outlandish and somewhat humorous. She infiltrates secret bases after being trained via montage — an actual, in-game montage. It’s mostly unconvincing, saved only by Page’s impressive ability to sell Beyond‘s script in earnest. The coupling of her belief in the story mixed with refined graphics (which illustrate the PS3’s capabilities in spite of the oncoming PS4 storm), make it work.

But the cover systems, the slowed-down action sequences, and the never-fail design corrupt Beyond‘s, for lack of a better word, soul. The run-and-gun moments, which are repetitious in circumstance and goofy no matter how many times I played, seem desperate and are completely out of place. There’s a version of Beyond: Two Souls somewhere, in someone’s dreams, that successfully mixes the basic gameplay structure with the dire militaristic situations. But that is not this game. Here, it’s just awkward.

Then there’s the side of Beyond that lets go of the clutter and the grandiosity; of the TRIPLE-AAA! notions of “action” and “adventure.” It’s a quieter side. It’s important. It resembles the intimacy that Heavy Rain achieved. In trying to convince a wider audience to shell out the dough for their new title, Quantic Dream forgot what made its first next-gen outing such a quirky, endearing tale: seemingly menial tasks coalescing into a close, personal narrative.

I didn’t care about drinking the orange juice in the beginning of Heavy Rain, but the action of doing it made it memorable. It’s a throwaway part, not even important to anything else that happens. But it’s also carefully designed. Delicate. I paid attention to every little detail. Much was the same with Beyond, whose gorgeous graphical presentation and attention to detail further support the game’s finer moments.

Which is why I only cared about Jodie when I spent time in her head: at a party when she’s a teen, pining after some pretty boy; under a bridge with homeless people, hopeless; having a fit and arguing with Aiden about needing her own space. That’s where the heart of the story was for me. That’s what Quantic Dream’s “move-toward-the-white-dot” design supported best. Beyond is at its most powerful when the simple controls, the undisturbed, slow and simple controls, allow for a personal story beat to resonate with the player. When the game takes a moment and just lets me chew on a situation (sometimes one that I helped craft), I was enthralled.

You know, kinda like a film.

I feel like I’m the only person in the world who loved this game. :/