Upon hearing my description of Power Grid, my sister shared her blatant opinion: “That sounds boring!” I was stung. Who wouldn’t want to preside over a vast network of power plants, upgrading from coal and oil to wind, solar, and nuclear energy? Who (other than my sister, apparently) would pass up the opportunity to be a grand financier/financière, becoming the Vanderbilt, the Ford, or the Carnegie of modern energy? Only a fool.

Upon hearing my description of Power Grid, my sister shared her blatant opinion: “That sounds boring!” I was stung. Who wouldn’t want to preside over a vast network of power plants, upgrading from coal and oil to wind, solar, and nuclear energy? Who (other than my sister, apparently) would pass up the opportunity to be a grand financier/financière, becoming the Vanderbilt, the Ford, or the Carnegie of modern energy? Only a fool.

I was exposed to Power Grid’s excellence at a friendly gathering. The host chose the game and I obligingly played. But afterwards, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I was obsessed with playing again. I had a crush on Power Grid. With good reason, mind you. First of all, the game is a feat of eye candy. Its premise is a two-sided board, each side equally colorful and carefully detailed. For Yanks, there’s a map of the United States and for Europhiles there’s a map of Germany (likely a tribute to designer Friedemann Friese’s motherland). Each map is divided into regions of various colors. On the U.S. map, for example, the northeast is colored brown, the midwest yellow, the northwest purple and so on. The colors aren’t just for show. They’re a clever way of scaling the game up or down from two players to six. A duo or trio plays with three regions, while a quartet plays with four, and a quintet or sextet with five. The genius of this scaling mechanism is that players using fewer than five regions may choose which regions to play with and which to omit. The only requirement is that the selected regions be adjacent. So if I’m playing a two-player game, for example, and I’m feeling down on the southwest I can avoid it by selecting the contiguous northwest, midwest, and southeast regions. This is a great touch; it expands gameplay options and gives players agency in tailoring their experience.

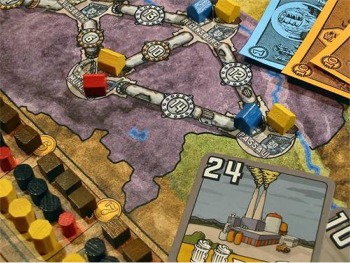

Each map is overlaid with pipelines stretching from one region to the next. Pipelines emanate from hubs in key cities like Miami, San Francisco, Stuttgart, and München. Each city hub in divided into thirds, each third representing a city section in which one player’s house may be placed. Some sections are more expensive than others and their availability for purchase depends on how far along the game has progressed. In Step 1, for example, only land priced at 10 Elektros (€) may be purchased for building. Because only one of the three plots per city costs €10, the first player to purchase prevents other players from constructing power plants in that hub until later in the game, when the land becomes more expensive (in Step 2, for example, €15 plots become available). Upon purchasing a city plot, a player places one of their 22 wooden houses to indicate that they’ve powered that city.

Each map is overlaid with pipelines stretching from one region to the next. Pipelines emanate from hubs in key cities like Miami, San Francisco, Stuttgart, and München. Each city hub in divided into thirds, each third representing a city section in which one player’s house may be placed. Some sections are more expensive than others and their availability for purchase depends on how far along the game has progressed. In Step 1, for example, only land priced at 10 Elektros (€) may be purchased for building. Because only one of the three plots per city costs €10, the first player to purchase prevents other players from constructing power plants in that hub until later in the game, when the land becomes more expensive (in Step 2, for example, €15 plots become available). Upon purchasing a city plot, a player places one of their 22 wooden houses to indicate that they’ve powered that city.

Player budgets must afford more than just city plots. Creating the vastest network of power plants is the ultimate goal of the game, which requires expanding from one city hub to the next. To do so, players must buy up pipelines from one city to another. Pipeline prices vary. At €3, the cheapest connections are easy on the wallet. The more valuable connections will set you back as much a €27, which can strain meager incomes.

But ownership of city plots and pipelines is nothing without power plants and the resources to fuel them. Capitalism reigns in this regard: resources and power plants are zero-sum and must be purchased on the open market in competition with other players. The market for plants is made up of power plant cards arranged in two rows of four. The first row comprises the four power plants up for auction (the “actual market”). The second row represents power plants that will come up for bidding (“future market”) by replacing power plant cards purchased from the actual market, which become part of each player’s three-card tableau (four in a two-player game). Once a player reaches that card limit, any new plant replaces older, less efficient, unwanted plants.

Each row of the market is arranged by price from least to greatest, with prices gradually increasing over the course of the game. Generally, price hikes indicate greater productive efficiency. For example, a power plant that requires two crates of coal to fuel one city costs only €4, while a power plant capable of powering seven cities with three crates of coal or three barrels of oil is worth €46; a plant needing only one cask of radioactive material to fuel six cities is priced at €39. Mind you, these are only base prices. A player who announces he’s going for plant 14 (with a base price of €14) might be outbid by his opponents.

When buying power plants, players must also consider the availability of the resource(s) needed to operate it. Resources are finite and must also be purchased on the open market. Resources are displayed in eight illustrated boxes on the bottom of the game board, plus four extra spaces for first-class, exorbitantly priced casks of nuclear material. The boxes indicate a price per resource purchased. Resources in the first box cost €1 per unit while units in the final box cost €8 per unit. Each box has the same capacity: three sacks of coal, three barrels of oil, one cask of radioactive material, and three cans of garbage. Players purchase resources in reverse turn order and players competing for the same resource drive up its price.

For example, if player 1 and player 2 both covet oil, and player 1 buys up all three barrels in the €1 box, player 2 is forced to purchase from the second box at €2 per barrel. The cost of fueling a power plant can skyrocket if a particular resource is only available in higher-priced boxes. At the beginning of the game, for example, cans of garbage may only be purchased from boxes seven and eight at €7 or €8 per can. If a player’s power plant needs three cans to run at capacity, she’s looking at a €21 bill (and potentially much more if she’s fueling multiple power plants). For this reason, nuclear and wind-driven plants are particularly valuable because they are self-powered (i.e., don’t require resources to generate energy). Resources are replenished after each full turn but rates of replenishment for each resource dip and surge asymmetrically over the course of the game.

After buying resources and building cities comes moneymaking. Players earn income for each house they’ve placed on the board provided they are able to power it using one of their plants. If a player has powered a plant with sufficient energy to supply two houses, for example, he earns €33 whereas a player able to supply 10 houses earns €105, and a player powering the maximum of 20 houses rakes in €150 per turn.

Game mechanics are relatively simple. The game is played in three “Steps,” which are essentially the three major stages of the game. Steps vary in the rate of resource replenishment and the plots available per purchase in a city hub (€10 plots are available in Step 1, €15 plots are added in Step 2, and €20 plots are added in Step 3). Each Step is divided into rounds, with each round subdivided into five consecutive phases: determining player order (player with the most cities in his network goes first); auctioning power plants; buying resources; building houses to expand city network; and bureaucracy, the phase in which players get paid.

So why am I so enamored of Power Grid? Primarily because it’s one of those rare games that is truly greater than the sum of its parts. Yes, the aesthetics are fabulous. The board and cards are of high quality, the illustrations top-notch. The player and resource pawns, made out of solid wood instead of hastily manufactured plastic, add a touch of nostalgia. The money is decadently designed and carefully printed. But it is the synergy of rules that makes this game truly excellent. Friese has cut this game from whole cloth, accomplishing a level of nuance demonstrative of true expertise and intellectual creativity.

That players auction plants in turn order during the first phase but purchase resources in reverse order in the second phase, for example, makes auctioneers wary of plants requiring resources the last player is likely to gobble up when he goes first in the resource-buying phase. That the number of plots available in each city hub corresponds to the Step (1, 2, or 3) forces players to spend their money on constructing vast networks rather than tight city clusters connected by the cheapest pipelines. That the highest-numbered power plant is discarded and replaced after each round guards against market stagnation and builds anticipation when existing options are unappealing. It is these minute but cleverly interwoven details that add variety, excitement, suspense, and strategic competition, both within a game and over multiple plays.

A word must also be said about the strength of the theme, which thoroughly permeates the game. My sister’s right: the game would probably be lame if the theme were half-hearted. Let’s be honest: power plants and energy production don’t sound particularly glamorous or intrinsically interesting to most folks. But once engrossed in the theme, the difference between wind and coal energy or the fluctuations in what once seemed a boring market suddenly seem thrilling. The theme is just as detailed as, and most evident in, the rules. What other game covers such fine-grained details as the characteristics of a hybrid power plant versus an ecological or fusion power plant? What other game teaches you that you can make energy out of garbage and makes you wonder where is that happening in real life?

My critiques of Power Grid are few. My main quibble is the generous influx of money each round. Unless a player is managing her selection of power plants and energy production incredibly poorly, she’s pretty much guaranteed piles of cash. The alleviation of financial pressure makes the game only moderately competitive. If I really want a power plant and have been managing my money with minimal attentiveness, I most likely have the ability (though perhaps not the desire) to outbid my opponent. If I buy a plant whose resources prove unexpectedly expensive, I cringe paying the higher price but then realize (a) it’s not real money and (b) I have and can expect a lot more of it. I suppose this could be remedied by reducing payouts, but this would involve redrafting a 21-figure payment schedule, which would probably involve some math if you’re going to do it right.

My second peeve is the availability of resources, which decreases substantially by the final third of the game. Resource prices boom, rising to what feels like an unreasonable level. This is likely why players earn so much money, but income still feels disproportionately high compared to resource cost. The game would benefit from a tighter and more meaningful correlation between resource prices and earnings. Similarly, it would have been nice for the distribution of power plants on the market to better reflect the number of players. In a two-person game it’s less likely players will be able to purchase the more technologically advanced plants because only two power plants are purchased (less if a player passes) per turn, which sharply limits the number of new plants entering the market. Perhaps Friese should have required that a certain number of low, mid, and high-priced plants be removed from the deck when playing with fewer players. Of course, players can enact a house rule requiring just that.

My final criticism is debatable. Many games divided into rounds dictate a certain number per game phase. However, in Power Grid the number of rounds per step will vary with each game. Step 2 is triggered when a player reaches a requisite number of functioning power plants in his network (10 in a two-player game, 7 in all others), and can be unpredictable until in the midst of play. In one game, players may dawdle in constructing their network or prevent other players from powering the plants necessary to trigger Step 2 by buying up all relevant resources. In another, players may vigorously pursue network expansion and pay little attention to other players’ resource needs insofar as they’re generally not in competition for resources. These factors mean playing time is unpredictable. For people hoping to squeeze a game into a busy day, Power Grid isn’t a particularly reliable option. Ditto for those times you’re entertaining guests with short attention spans. Still, if you have the time, the unpredictability of game length just adds another inventive twist to help keep the game fresh over time.