We can’t escape our past.

– Joel

What’s left when everything is gone? What’s left when we don’t have jobs to go to? Careers to pursue? What’s left when we can’t read about the forecast or learn about the latest news? What happens when there’s no music or television or media? What’s left when we have nothing by the last of whatever it is that makes us human? What’s left when all we have is something pathetic, clenched, and sacred? What do we do? How do we react?

The ideas of The Last of Us were unclear at first. Like developer Naughty Dog’s Uncharted franchise, The Last of Us seemed borne of something on a track. What I mean is, while it offered segments of choice in terms of advancement, at the end of the day, it didn’t seem to stray from where it wanted to go or wanted to say. And that bothered me. Here is a game that presents choice in how I execute levels. It gives me different degrees of strategy: the tools I use, the weapons I choose to enhance, the value of human lives. This was all presented on a platter. But, then, the story remained stubborn and, at times, ignorant of these mechanics.

The more I’ve mulled over this idea of what it means to have agency in the game’s story, the more I realized I didn’t. The Last of Us wasn’t interested in me. Yes, it’s a game. Yes, it has gaminess. And yes, I’d restart areas in order to get through without error or detection. But, honestly, that didn’t matter. There was something The Last of Us wanted to say regardless of my time investment or tactical approach. It was cruel. It was selfish. And, damn it all, it was right.

A boy and his things

Joel is not a good man. As the protagonist, he’s a shade uglier than the ugly of other anti-heroes like Malcolm Reynolds or Tom Cruise’s unfortunate Ray Ferrier in War of the Worlds. Joel takes what’s his. He wants to survive, above all else. In the game’s prologue, set 20 years prior to his tale with Ellie, we learn why. And from there his grit and grey were in full bloom. While unconvincingly fit for what I assume is a 50-something-year-old, there’s a tiredness to Joel that seeped out into my living room. His worn-in fatigue, pinched with spikes of fury, enervates.

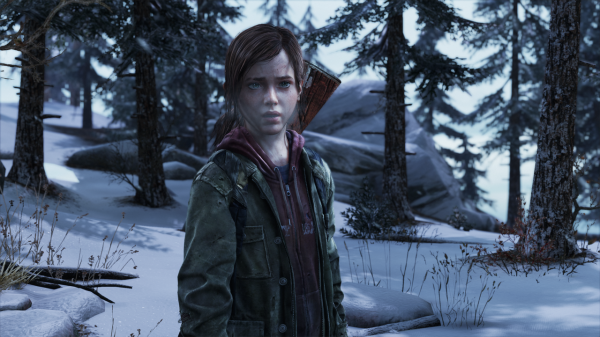

It’s left to Ellie, Joel’s teenage escortee, to bring life and love to the game. Ellie is curious and alive. She first comes into the game, not afraid or understanding or sad, but angry. She doesn’t want to team up with Joel. She doesn’t want to have anything to do with him, nor does he with her. Still, the relationship develops with human moments that exercise Naughty Dog’s true gift (not the explosions and expertly-crafted set pieces), the dialogue. The silences between characters are poignant. Thoughts and emotions don’t need fatty words filling in the gaps. A few seconds reading Ellie’s or Joel’s or anyone’s face does just fine. Games industry: please give more of this.

Still, it’s easy to get the wrapped up in the father/daughter, guardian/child relationship The Last of Us is keen at developing when there are so few children (or other female) characters in the game. In Rian Johnson’s “Looper,” Joseph Gordon-Levvitt’s Joe is ruminating over the violence and actions of the events that lead him to that point in his life. “It’s just men trying to figure out what they would do to keep what’s theirs, what they got. See what kind of men there is.”

The same idea permeates The Last of Us. The game is predominately occupied by men in a hunt to secure their own wealth, their own advantages. Joel is no different, which makes Ellie all the more compelling. In fact, the majority of the main female characters in the game are as they strive for something progressive and selfless while the majority of the men operate in fear or anger. Ellie, in a sense, brings the humanity out of Joel. What little is left, anyway.

Hands on the wall

There are sturdy moments of exploration and exposition, wherein characters jog through households, calling out to one another. The desperation of discovering another box of ammo or a roll of tape adds to the direction of the game. It’s there, but there’s also a frustrating sense of aimlessness. That while there is indeed a destination for our heroes, if they even are that, to get to, there isn’t propulsion behind their movements. The design of the game leaves each area open-ended. I’d inspect hallways, bedrooms, bathrooms. I’d use toilets, I’d rummage through cabinets. Maybe there’s a note or a bottle of alcohol. Maybe I’ll get to craft a med-kit or a Molotov, but it’s never rewarding.

The discovery of items in The Last of Us gives you weapons and health. And that provides no relief. The looming sense of worthlessness subsists in the game’s emptied neighborhoods. Even the stark scenery, glowing with the crisp sun light washing in the greens of trees and the dirtied camera lens, makes you feel hopeless. That gorgeous landscape, left to me to appreciate or ignore, is the source of all this. The death and dissembling of society in The Last of Us is courtesy of a fungal virus that infects humans through toxins. Slowly, these people lose any sense of self, breaking apart into a twitchy, frightening corpse, half-alive.

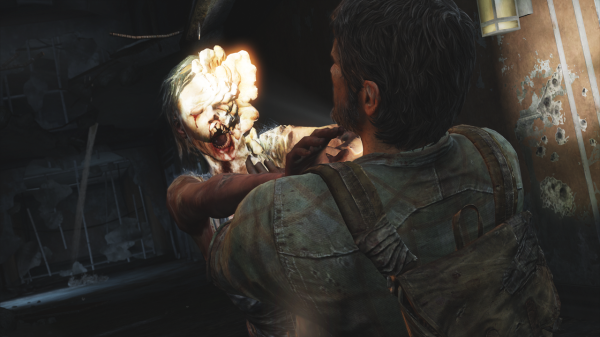

Joel and Ellie encounter these things. Some are in the process of change, still able to see and hear, still human-looking. Some are too far gone to have a face. They’re contorted frames shuffle in the distance. They only respond to sound. Called clickers, for the sound of their repulsive groans and guttural noises, these monsters only need one moment to grab someone and rip out the more tender bits of their neck.

When encountering clickers and the more-human hunters, stealth always seemed like the best option. I’d craft a shiv, hunch down, hold down R2 for my radar sense (allowing me to hear and see where everyone, or everything, was in the room) and slowly creep through. Often, things would go wrong. I’d be heard or seen. I’d reset. I hardly ever let a situation play out if I was caught. I wanted to make my way through the game without being detected. I thought it was the right way. And whenever I was in a stealth situation with human characters — no infected — I did my best not to get rid of them. I’d try to let everyone live, thinking that it was the moral thing.

I projected my own values onto the game. As I said, The Last of Us wasn’t interested in that.

Through the woods

Learning periods in games are never fun to get through. The awkward, teenage-years of an early gaming experience lead to failed levels, poor mechanical understanding, and lots of retries. In The Last of Us, this isn’t anything different. However, the added effect of dreariness, the powerless nature of the narrative, adds an inexcusable amount of lulling to the experience. There were hours when I felt on edge, waiting for the next vicious moment to terrorize whatever peace I came across. It was unsettling, which is important, but not motivating.

That rising action leads to a mid-point climax. There’s a powerful segment that pivots the narrative from inspired to hushed. The latter-half of The Last of Us is a tense slither through maturity and horror. Like someone watching a silent film and every once in a while plucking at an unsettling violin string. It’s a brilliant second half of a game that prepares itself for an ending without a clear message.

The madness leading up to final moments of The Last of Us illustrate a clawing retort to the systems and assumptions I had about the game. Some of the characters were more brutal than I imagined. The force at which the story escalates is frightening, even more so when I finally submitted to the fact that not every enemy I came across would survive. Eventually, I betrayed my no-kill policy. Eventually, the story pushed through my original intentions.

I had a similar experience when I played Spec Ops: The Line. During that game, in which you play as a marine on the hunt through Dubai for your former commander who has allegedly gone rogue in the sands of a ruined city, my patience and posture in play shriveled. In The Last of Us, I fought the urge to submit to more barbaric decisions up until the end, until I didn’t even realize what was happening until it was happening. Ellie. Joel. The infected. The humans. What was left? All that I had tried to preserve, did it even add to my experience?

I collected letters, learned about a man named Ish and his foolhardy desire for love and the accompaniment of others. I saw the result of this man’s betrayal of what he had originally set out to do: survive. It was ugly. Joel wants to survive. He wants to keep what’s his. He fought for it and he’ll keep fighting for it. Me, as the player, really has nothing to do with him. I won’t change his mind. I’ll just alter how much he’ll fight for his life.

First and Last

The opening monologue to Danny Boyle’s “Trainspotting” (also featured in Irvine Welsh’s book on which the film is based) is an ignorant simplification of how the majority of people are predictable and lost. It’s delivered courtesy of Scottish teen living life on fumes and in the troves of heroin. Renton, played by a wispy Ewan McGregor, barks out: Choose life… but why would I want to do a thing like that?

It’s a cerebral portrait of what we consider “waste,” of what we believe is right and what is wrong. Much like the themes of The Last of Us, “Trainspotting” asks whether or not they’re worth our time.

Love, companionship, loss. The genius of The Last of Us is its muted presentation of these themes. There aren’t glowing neon lights telling us to understand (dissimilar to “Trainspotting,” which, in order to address the questions of life and worth, has a prop baby crawl across the ceiling above a mentally-collapsed Renton, who recently kicked a heroin addiction by going cold turkey). The grain on the lens of my camera muddies the messages of this tarnished world. Most of the characters keeps those things buried… deep. Bringing them up in the real sense, being vulnerable and sharing a feeling, becomes something exploited. It’s weak. They keep that hidden, Joel especially. When he starts sharing his thoughts or dwelling on the meaning of earlier events — when he starts living in the past — that’s when he could lose it. That’s when what he needs to do could fall prey to what he wants to do.

I played the majority of The Last of Us like this. In the past. I kept reloading my game, trying to perfect my stealth. It wasn’t until I let go of my previous actions that I was able to move forward. That’s when I started seeing the world like Joel. And it was ugly.