A game tells a story with its lighting, its artistry, its character models, its vocal dialog, and all the other computer bits that Pixar still rocks hardest in the world of digital media. More intriguing, I (and the rest of the gaming thoughtful) argue, is the story a game tells through its interactivity. The rebel that this vehicle creates is a lunatic; mass murders and amoral thievery aren’t his whimsy, they are his goal.

Seasoned gamers (those grumpy old men of fandom) know all about the resulting dissonance. Hell, if we haven’t heard it from the parent, the spouse, or the teacher, we’ve at least heard it from Fox & Friends, from the quivering finger of the media looking for a scapegoat. They see games for their truest component, and they ask for justifiable accountability (often to an unreasonable degree, but who’s counting?).

So Christopher Park, the enigmatic independent human-bot developer behind the AI War series, decided to make a game that might change the bloody tide of modern gaming, taking inspiration from Mojang’s constructive world of Minecraft. He and the crew at Arcen Games had this grand plan for evolving environments, manipulated by the player; a 2D world shaped by tiny sprites, pushing back against the bigness of “the earth” to discover a sense of empowerment in carving out a unique gorge in an ever-changing landscape.

Then Terraria released on Steam to wild success and Chris said, “Poop.”

Re-enter the player-psychopath, roaming a persistent, procedurally generated countryside and butchering scores of skeletons, sea worms, energy wisps, and whales for personal benefit. Arcen Games’ PC adventure/platformer/RPG A Valley Without Wind follows an infinite supply of glyphbearers as they scour Environ (circa 888, but time is broken so whatever) for glyphs and resources to rebuild society and free the subjugated people from hostile robot overlords and an unforgiving climate. There is a lot of magic-wielding, jumping, puzzling, and dying, and it’s all meant to rip apart the pillars that hold it up. Confused? So is the game.

The first thing a player will notice about AVWW is that the music is awesome. Pablo Vega did a fantastic job blending live instruments with surprising, somber, 8-bit melodies to generate one of the most haunting (in a good way) soundtracks this year. Sound effects are about as standard as they come, and dialog is exclusively communicated through text (psh, indie PC developers, right?), but the music nails that overwhelming sense of isolation and panic in the dark bowels of the Grasslands Cave #2.

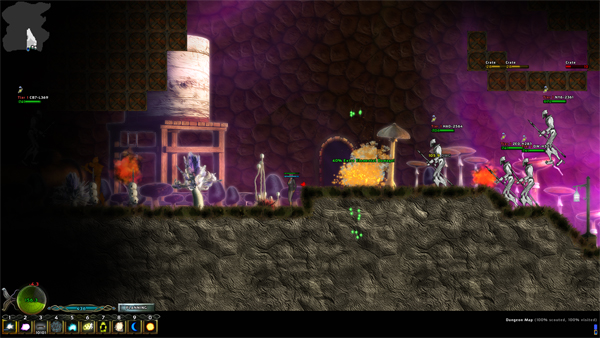

Which brings me to Grasslands Cave #2. For a game by a studio with as much heart as Arcen Games, AVWW relies so little on theatrics. In fact, the whole thing was free-to-play for a several months prior to release for beta testing. Enemies are larger or smaller versions of their counterparts, who, like abilities, level up by Tiers, 1-5. Bosses are Overlords or Lieutenants or not-even-ranked skeleton robots. Procedural generation, it seems, has its generic price.

In exchange for the repetition that dominates AVWW, the player is given an exhaustive array of abilities – ranging from the summoned boulder toss, to generating platforms, to fireballs, to zombie partners, to teleportation – and an endless world to explore. That’s actual endlessness, by the way… as in the world has no end. To call this a game about exploration would be disingenuous because it is digital exploration incarnate. Where Terraria has its user-generated levels, AVWW has its computer-generated wasteland. It turns out, computers can make way more levels than users.

“Keep looking hard enough,” it coaxes, “and you’ll become the character you’ve been grinding for.” It’s here that the game undercuts itself, cleverly. Rather than attribute abilities, earnings, or structures to a mortal in-game character, they reside with the player. The avatars, then, are as disposable as bat-kings, though their ghosts may haunt the player in death by resurrecting as ghoulies. The player fights an army of past mistakes with an army of future mistakes, wielded as callously as the lives of the enemies he destroys.

When the line between player-character and player-target are this indefinite, AVWW takes the burden of the psychopath off of the psychopath and into my murderous hands. Chris and his game see us honestly, gamers. They see what we hope to become – virtually speaking – and what we’re willing to do to get it. They enable our carnage, and thank us for it with free DLC (on launch day, I downloaded three separate patches for the game, and noticed another large patch with new missions and enemies released at the time of writing).

The question with AVWW isn’t so much whether you’re an awful person, it’s how awful will you let yourself be. If it were up to Chris, you’d be endlessly, repetitively awful.